Intrinsically Motivated

Modular Multi-Goal RL

09 April 2019

In collaboration with Olivier Sigaud & Pierre-Yves Oudeyer. Reproduced from our team's blog .

Introduction

In Reinforcement Learning (RL), agents are usually provided a unique goal, well-defined by an associated reward function that provides positive feedbacks when the goal is fullfilled, negative feedbacks otherwise. If a domestic robot sets the table, it is rewarded, if the plates are on the floor, it is not. The objective of that agent is to maximize the sum of collected rewards.

In the more realistic open-ended and changing environments, agents face a wide range of potential goals that might not come with associated reward functions. Such autonomous learning agents must set their own goals and build their own curriculum through an intrinsically motivated exploration. They must decide for themselves what to practice and what to learn. Because some goals might prove easy and some impossible, agents must actively select which goal to practice at any given moment, to maximize their overall mastery on the set of learnable goals.

This blog post presents CURIOUS, an algorithm rooted in developmental robotics that builds on two main fields:

- Multi-goal RL. Agents traditionally learn to perform one well-defined goal. On the contrary, Multi-Goal RL trains agents on a goal-parameterized setup. Instead of training a robot to bring the TV remote at this special spot on the table, we can now train it to bring it at any given location (goal), in the living room, on the sofa etc. Learning about a precise goal benefits learning about others as well, which speeds up learning.

- Curriculum Learning. When facing different possible goals (e.g. going to the kitchen, fetching the remote, cleaning the floor), the agent needs to prioritize and decide which goal to practice at any given moment. Developmental Robotics presents mechanisms to help this goal arbitration. Optimizing for learning progress for example, enables an automatic curriculum to emerge. First, train on simple goals. When they are mastered, move on to others where progress is made.

All details can be found in the paper. The algorithm and the environment can be found on Github.

The Problem of Intrinsically Motivated Modular Multi-Goal Reinforcement Learning

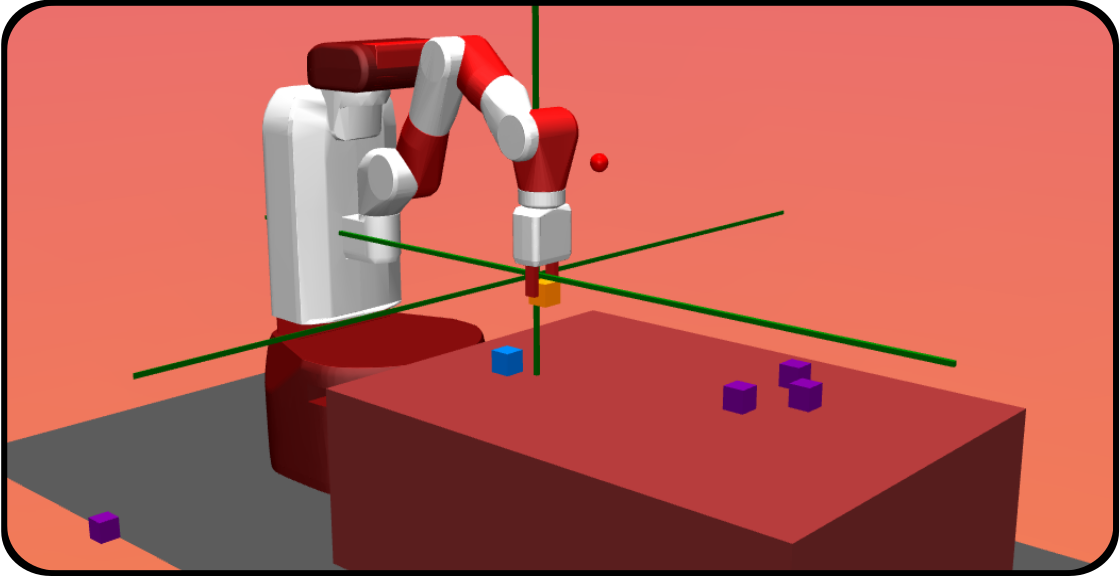

Modular Multi-Goal Fetch Arm: an environment with multiple modular goals with various levels of difficulty, from simple to impossible. One module correspond to a type of goals (Reach, Push, Pick and Place, Stack, Push out-of-reach cube). For each module there is an infinity of potential goals (targets).

Agents in the real world might face a large number of potential goals that might be of different types. A domestic robot might want to clean up a table, to prepare the meal, to set the table etc. Some of these goals might be regrouped into modules where particular goals are seen as targets of a same general behavior: e.g. “move the plates” can be seen as a module where particular goals would be “move the plates on the table”, or “move the plates in the cupboard”. The modules here can be more generally defined as constraints on the state or trajectory of states. “Move the plate” requires a modification of the position of these plates, the particular goal requires an additional parameter speciying where.

This modular multi-goal setting is simulated in our Modular Multi-Goal Fetch Arm environment. Adapted from OpenAI Gym’s Fetch Arm environments, the robotic arm faces a table and several cubes, and can decide to Reach a 3D target (goal) with its gripper, to Push a cube on a 2D target, to Pick and Place a cube on a 3D target or to Stack one cube on top of another. Several out-of-reach cubes are added to the scene to represent distacting modules: modules that are impossible to solve by the agent. These cubes are moving randomly and perceived by the agent.

This problem is seen through the lens of the Intrinsically Motivated Goal Exploration Process (IMGEP) framework. The agent decides itself which goal to target, which goal to train on at any given moment. It is intrinsically motivated to set its own goals to explore its surroundings, with the objective of mastering all goals that can be mastered. The number of potential modules might be large, some goals might be easy, others difficult or even impossible. This advocates for curriculum learning mechanisms to enable efficient experience collection and training.

Previous Work

As mentioned above, CURIOUS integrates and extends two lines of research: Multi-Goal RL and Curriculum Learning.

The state-of-the-art Multi-Goal RL architecture is Universal Value Function Approximators (UVFA). It proposes to condition the policy (controller) and the value function (predictor of future rewards) by the current goal in a multi-goal setting. This enables to target goals drawn from a continuous space (e.g. target maze location, target gripper position) and efficient generalization across goals. Hindsight Experience Replay (HER) proposed to generate imagined goals to learn about, when a trajectory did not achieve its original goal (counterfactual learning, see figure below). UNICORN introduced a discrete-goal-conditioned policy to target a finite set of discrete goals and used discrete counterfactual learning (replacing the original goal by a random imagined goal from the goal-set). All these algorithms are based on UVFA and the idea of having a controller that uses the goal as input. Although the term goal is defined quite generally in the paper, previous research has mostly used simple goal representations. In the original UVFA paper, a goal is a target position in a maze, in HER it is a 3D target position for the gripper, in UNICORN it is the type of object to reach. Furthermore, the multi-goal RL community has focused on goal defined externally, provided by the experimenter for the agent to execute.

Counterfactual Learning with HER. From OpenAI blog .

CURIOUS builds on the developmental robotics research and considers the agents to be empowered to select their own goals. We use previously defined mechanisms for autonomous curriculum generation. As in MACOB and the IMGEP framework, CURIOUS tracks its competence and learning progress on each module and maximizes the absolute learning progress based on a multi-armed bandit algorithm. Learning progress was previously used in combination with memory-based learning algorithms. For each episode, the agent stores a pair made of a controller and a description of the outcome of the episode. This type of algorithm is hard to scale because of memory issues and is generally quite sensitive to the distribution of initial conditions.

The CURIOUS agent extends these two lines of work with two main contributions. First, it enables to target multiple modular goals settings in a unique controller by proposing a new encoding for modular goals. The policy is therefore conditionnd by both the current module and the current goal in that module, enabling efficient generalisation across multiple goals of different types. Second, we use mechanisms based on learning progress in combination with an RL algorithm. In addition to using learning progress to select the next module to target, we also use learning progress to decide which module to train on.

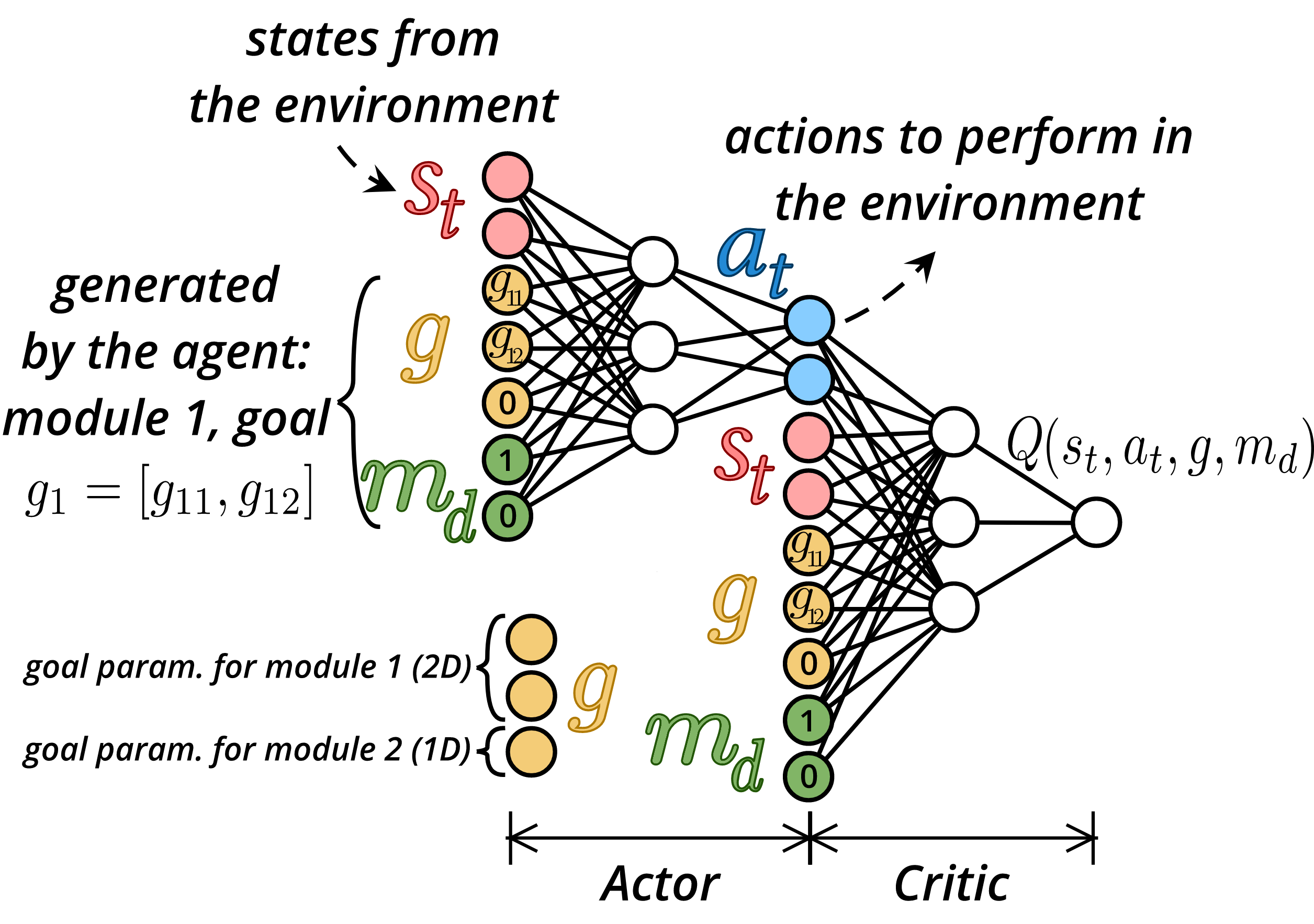

A Modular Goal Encoding: M-UVFA

The most intuitive way to target multiple modular goals would be to use a multi-goal policy for each module. We call this architecture Multi-Goal Module Expert (MG-ME). With CURIOUS, we propose the Modular-UVFA encoding to target multiple modular goals in a single policy. The input of the policy (and value function) is now the concatenation of the current state, a one-hot encoding of the module and a goal vector. The goal vector is the concatenation of the goals in each module, where the goals of unconsidered modules are set to 0. In the toy example presented in the figure, the agent targets module \(M_1\) \((m_d=[1, 0])\) out of 2 modules and targets the 2D goal \(g_1 = [g_{11}, g_{12}]\) for module \(M_1\) e.g. Pushing the yellow cube at position \(g_1\) on the table. The underlying learning algorithm is Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG). We use discrete counterfactual learning for cross-module learning and HER for counterfactual goal learning. This consists in replacing the original module descriptor and goal in the transition by others. HER replaces the original goal by an outcome achieved later in the trajectory. UNICORN replaces the original goal by a random goal from the finite finite goal-set. In other words, our agent can use any past experience to train on any goal from any module by pretending it was targeting them originally.

Actor-Critic networks using the M-UVFA architecture: In green a discrete one-hot encoding of the current module. In yellow the goal vector, concatenation of the goal vectors (targets) of each module. When a module is selected, only the sub-vector corresponding to that module is activated.

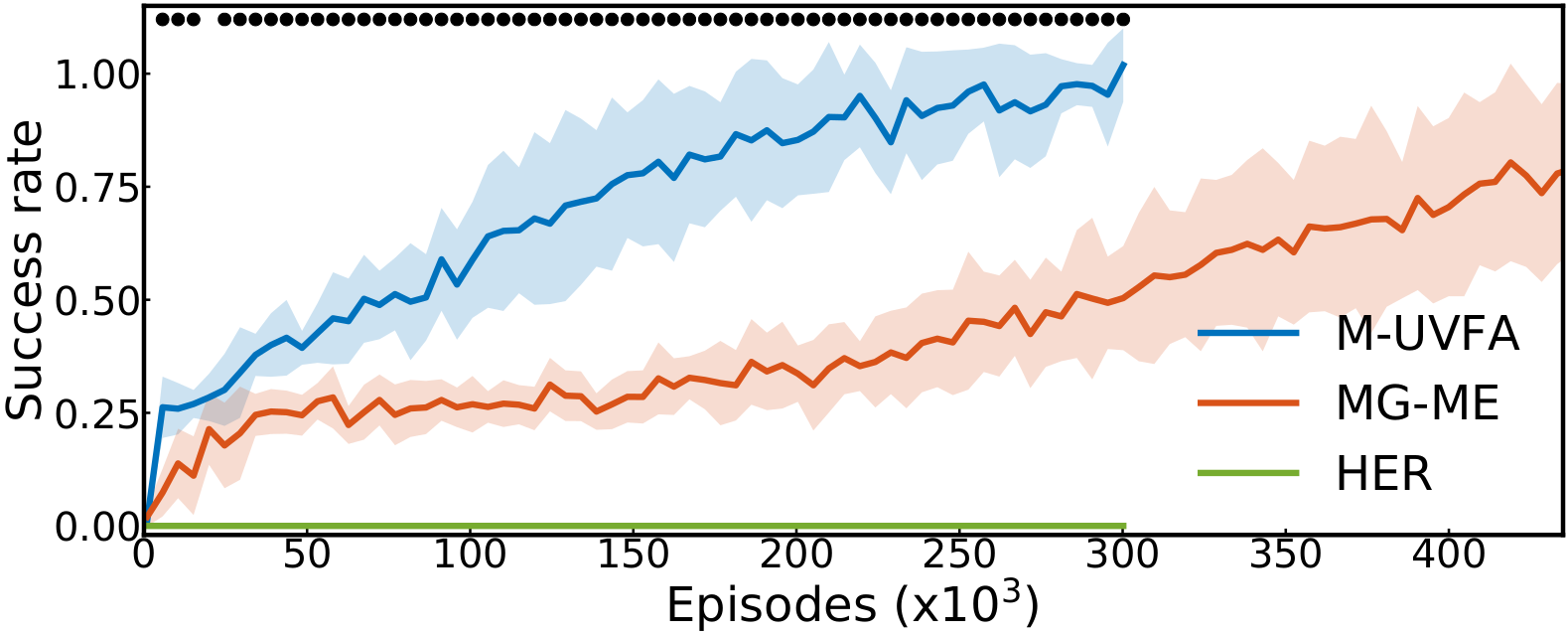

The figure below demonstrates the advantage of using a unique policy and value function to target all goals from all modules at once. We run 10 trials for each architecture on a set of 4 modules and report the average success rate over the four modules. As a sanity check demonstrating the need to use a modular representation of goals, we try the HER algorithm, where goals are drawn from a flat representation (e.g. put the cube at position \(x_1\) while reaching position \(x_2\) with the gripper). As almost none of these goals can be reached in practice, the performance of HER stays null.

Impact of the policy and value function architecture. Average success rates computed over achievable modules. Mean +/- standard deviation over 10 trials are plotted, while dots indicate significance when testing M-UVFA against MG-ME with a Welch's t-test.

Automatic Curriculum with Learning Progress

|

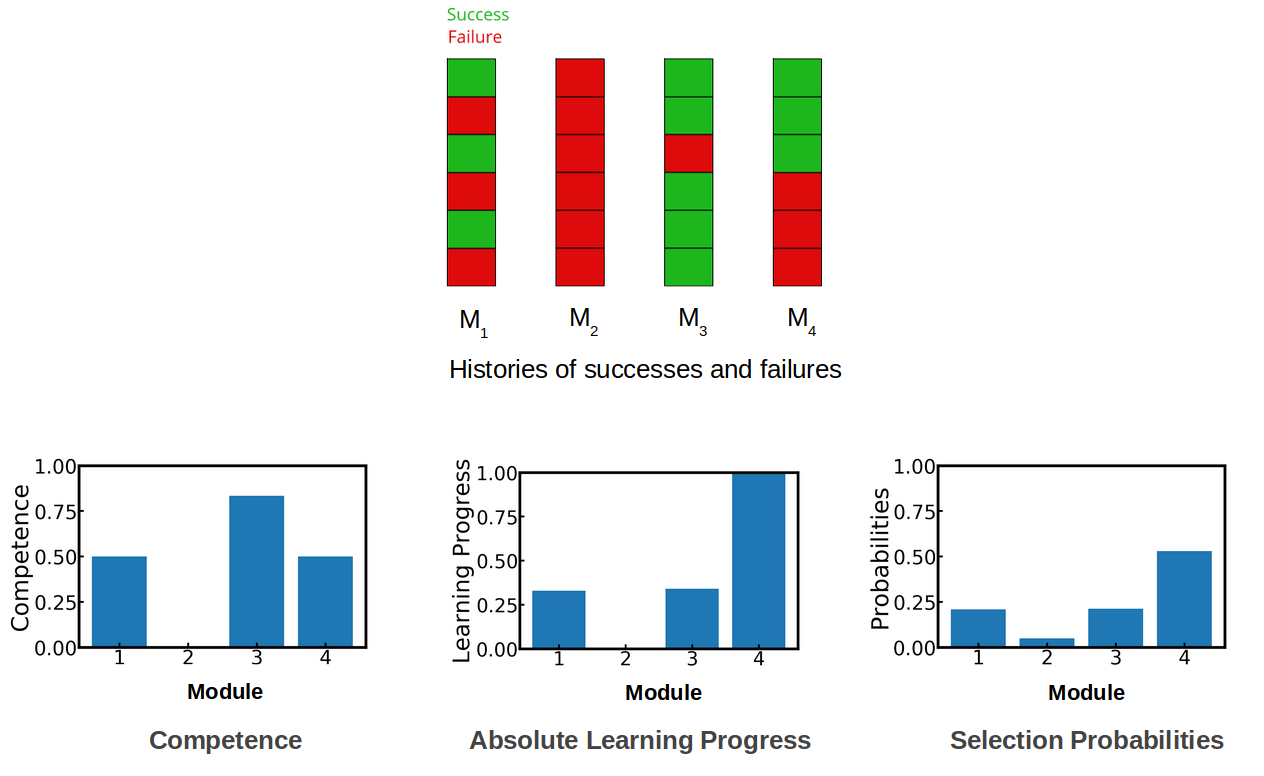

Computing competence, learning progress, and module probabilities.. The agent keeps track of past successes and failures using a limited_size history per module (N=6 here)(top). Using these histories, it can compute its own competence on each module using the success rate over the last 6 attempts (left). It can also track its learning progress as the difference between success rates computed over the last 3 attempts and the previous 3 attempts. Finally, the agent computes selection probabilities based on these measures (right).

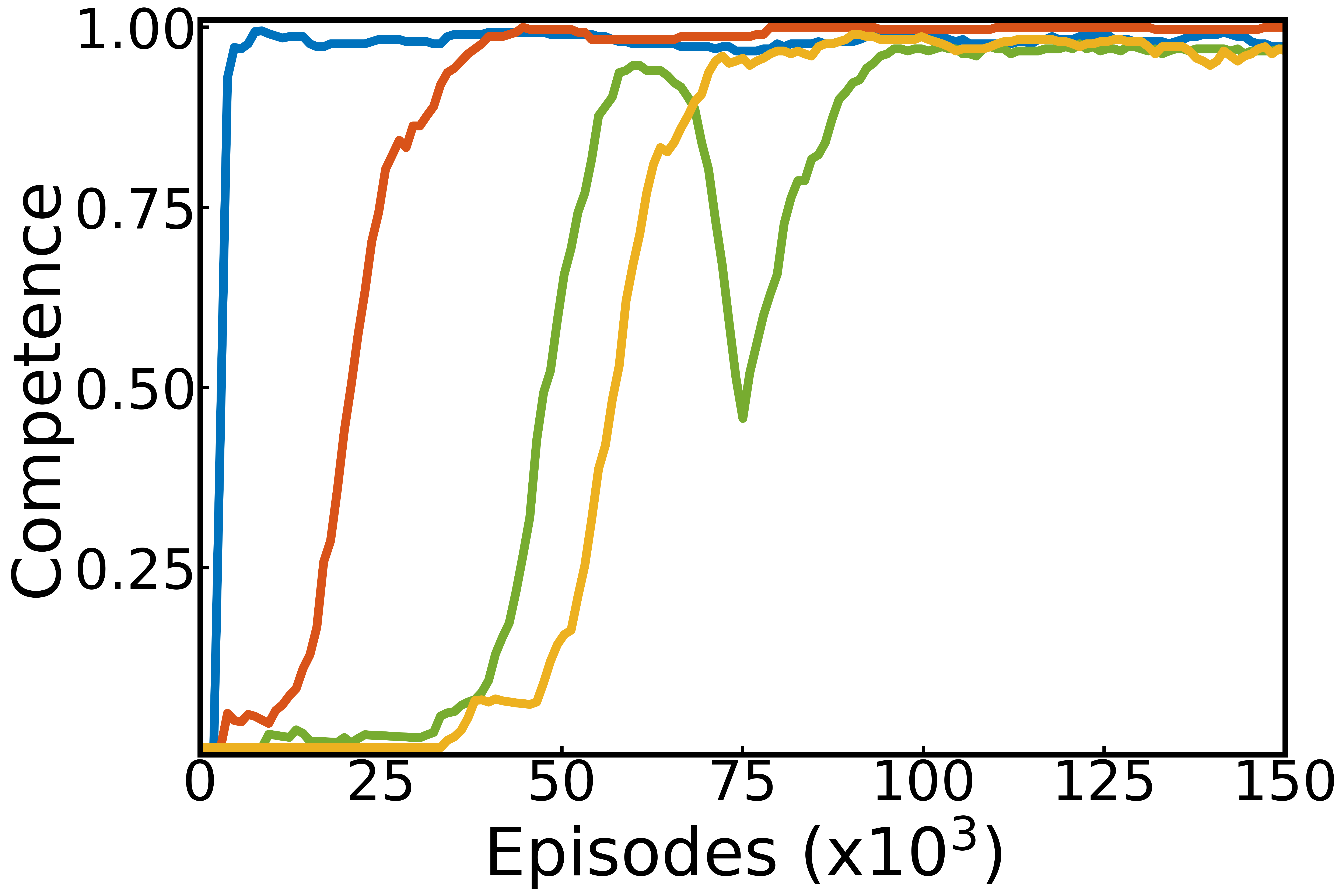

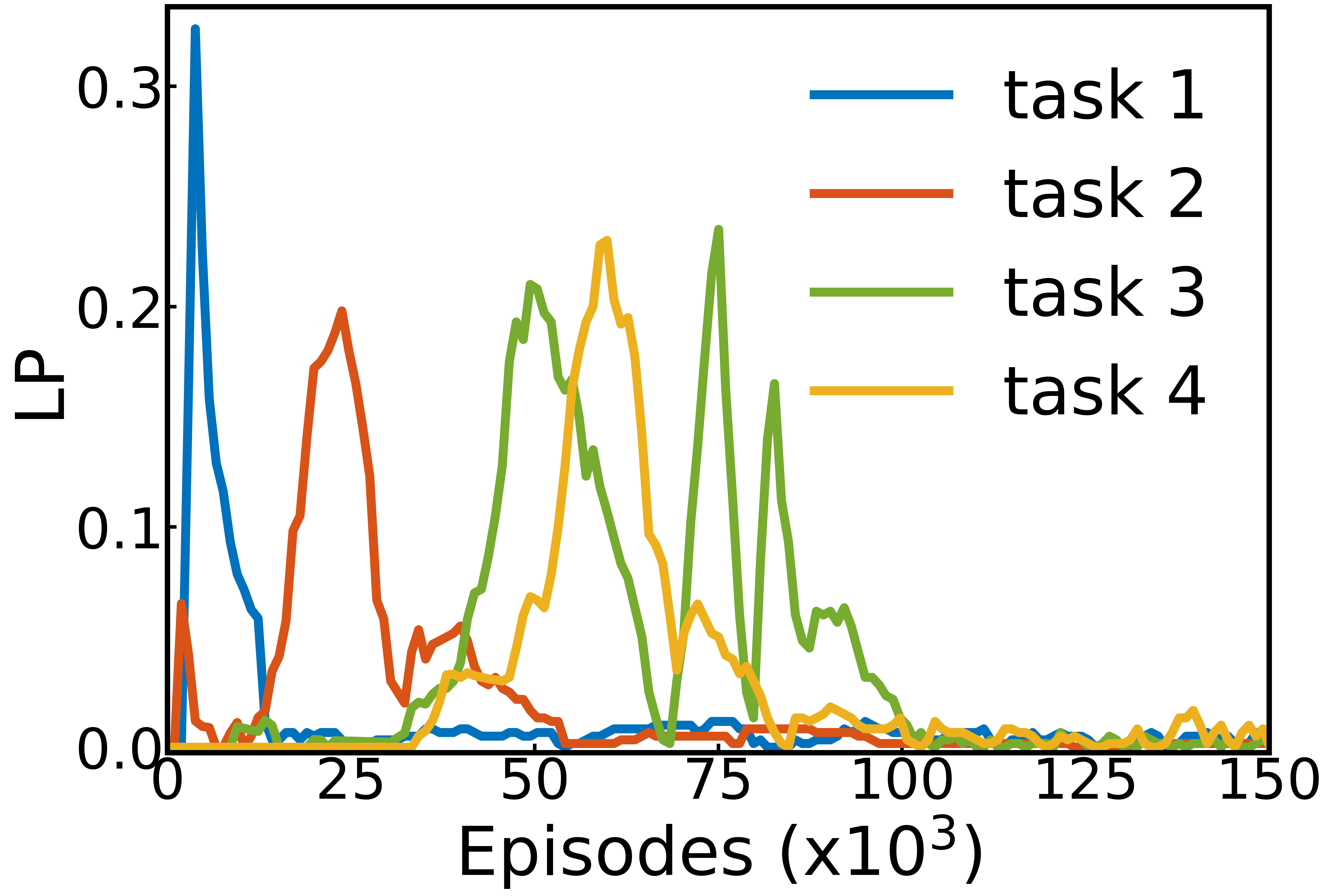

Our agent tracks its competence and learning progress (LP) on each module. To do that, it performs self-evaluation episodes without exploration noise, and records for each module the list of past successes and failures. The competence in a module is simply the success rate over the recent history. The learning progress is defined as the derivative of the competence, and is empirically computed using a difference of success rates computed over two consecutive and non-overlapping windows from the recent history. The figure below presents an example of these self-evaluations.

The learning progress measures are used for two purposes:

- To select which module to target next (as in MACOB).

- To select which module to train on (new).

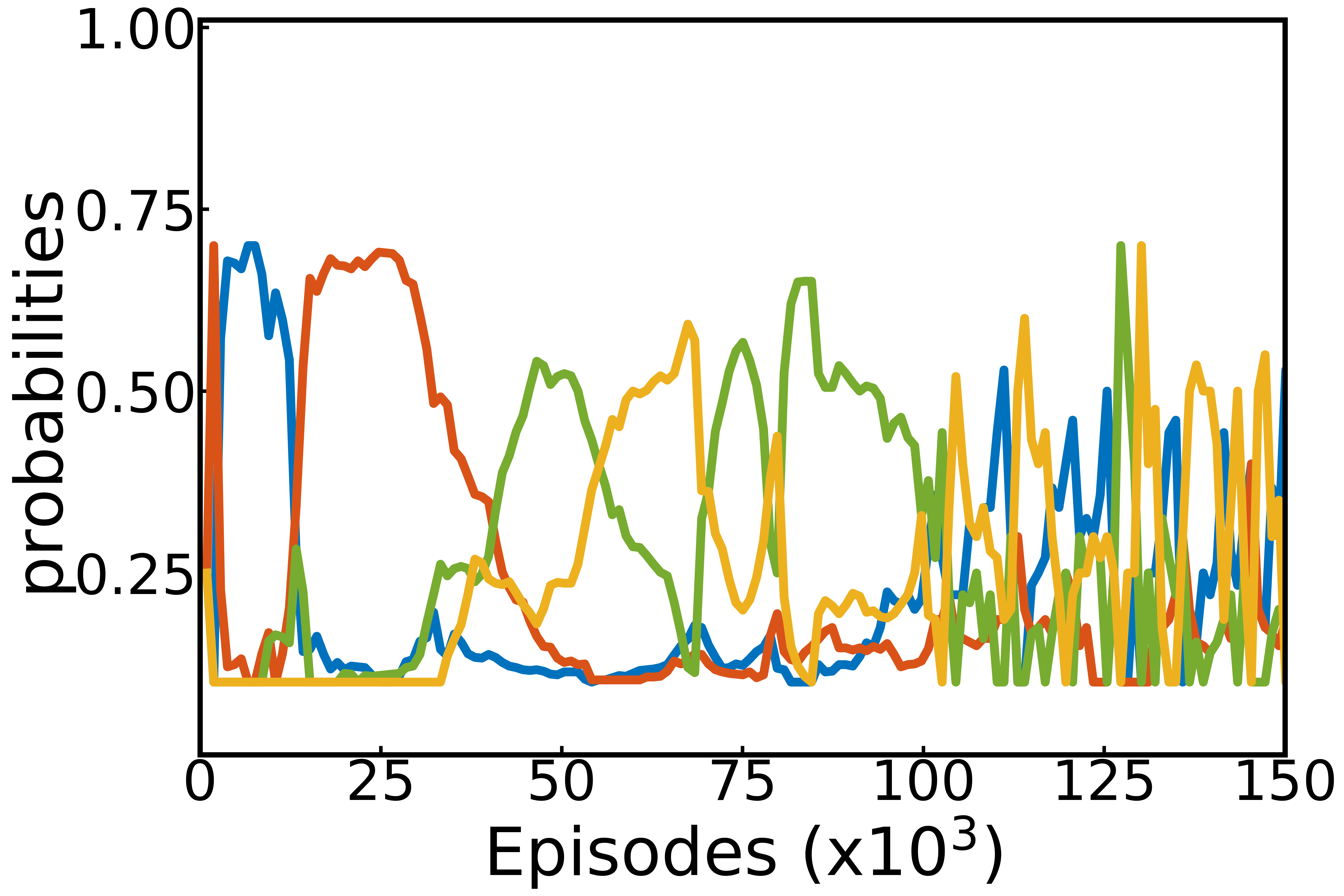

The problem of module selection can be seen as a non-stationary multi-armed bandit problem, where the value to maximize is the absolute learning progress. We compute selection probabilities using an epsilon-greedy proportion rule based on the absolute measures of learning progress:

\[p(T_i) = \frac{\epsilon}{N} + (1-\epsilon) \frac{\mid LP(M_i)\mid}{\sum_j \mid LP(M_j)\mid},\]where \(N\) is the number of modules, \(LP(M_i)\) is the learning progress computed on module \(M_i\).

These probabilities are used to select the next module to target, and to bias the counterfactual learning of modules. Substituting the original module by another enables to focus learning on the substitute module. When the agent thinks about that time it was trying to lift the glass but tries to pretend it was pushing the glass, it learns about pushing the glass. If the agent tries to think about many experiences with the imagined goal of pushing the glass, it might learn how to do it. It might even learn that goal without having ever targeted it before! Using LP measures enables the agent to control on which module to focus its learning. It first focuses on simple goals where it is making progress. When they are mastered, they become less interesting and the agent focuses on new goals. Following the learning progress automatically builds a curriculum learning strategy.

The figure below shows the competence, learning progress and selection probabilities computed internally by the agent over the whole run. It is like having access to the inner variables it uses to make decisions. We interpret these curves as a developmental trajectory of the agent. First, it learns how to control its gripper (\(M_1\), blue). When it knows how to, learning progress drops, making this module less interesting. It then focuses on another module where it has started to make progress (pushing the cube, orange). Finally, it learns to pick and place and stack cubes (green and yellow respectively).

Around \(75.10^3\) episodes, the agent detects a drop in its competence in the Pick and Place module, this triggers an increase of the absolute progress which ultimately results in a renewed focus on that module, enabling to mitigate the performance drop. Using the absolute value of learning progress helps to resist forgetting.

|

|

|

Competence, learning progress and developmental trajectories: Left: competence for each module in one run of the algorithm. Middle: corresponding absolute learning progress. Right: corresponding module probabilities.

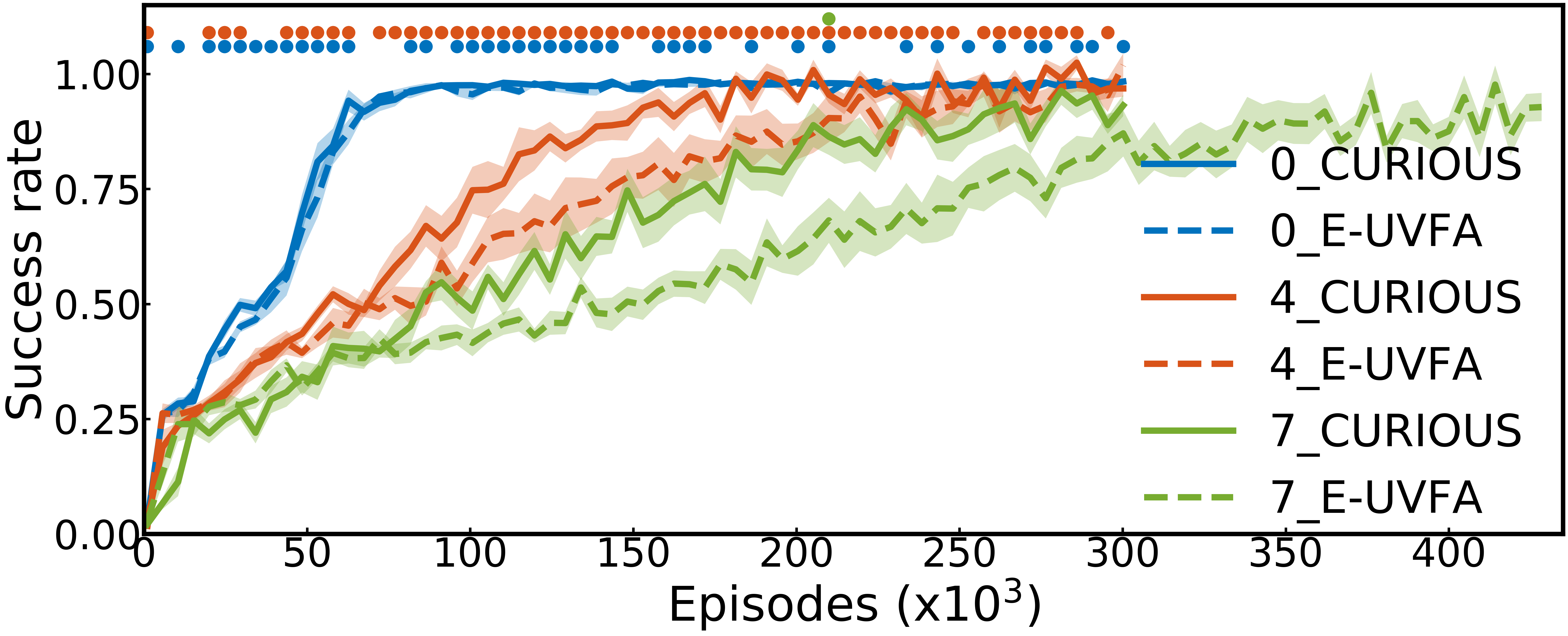

Resilience to Distracting Tasks

In the real world, not all goals can be achieved. We simulate this with extra modules where the agent needs to push out-of-reach cubes on 2D locations. As these modules are impossible, the learning progress measure stays flat, which enables the agent to focus on more relevant modules. When the number of distracting modules increases (0,4,7) in addition to the set of four modules described earlier, the use of the learning progress module selection and replay (CURIOUS) improves over the random module selection and replay (M-UVFA only).

Resilience to distracting modules: Different colors represent different number of distracting moduesl (Pushing an out-o-reach cube). There are four achievable modules. Dots indicate significant differences between CURIOUS (intrinsically motivated) and M-UVFA (random module), using a Welch's t-test and 10 seeds. Mean and standard error of the mean plotted.

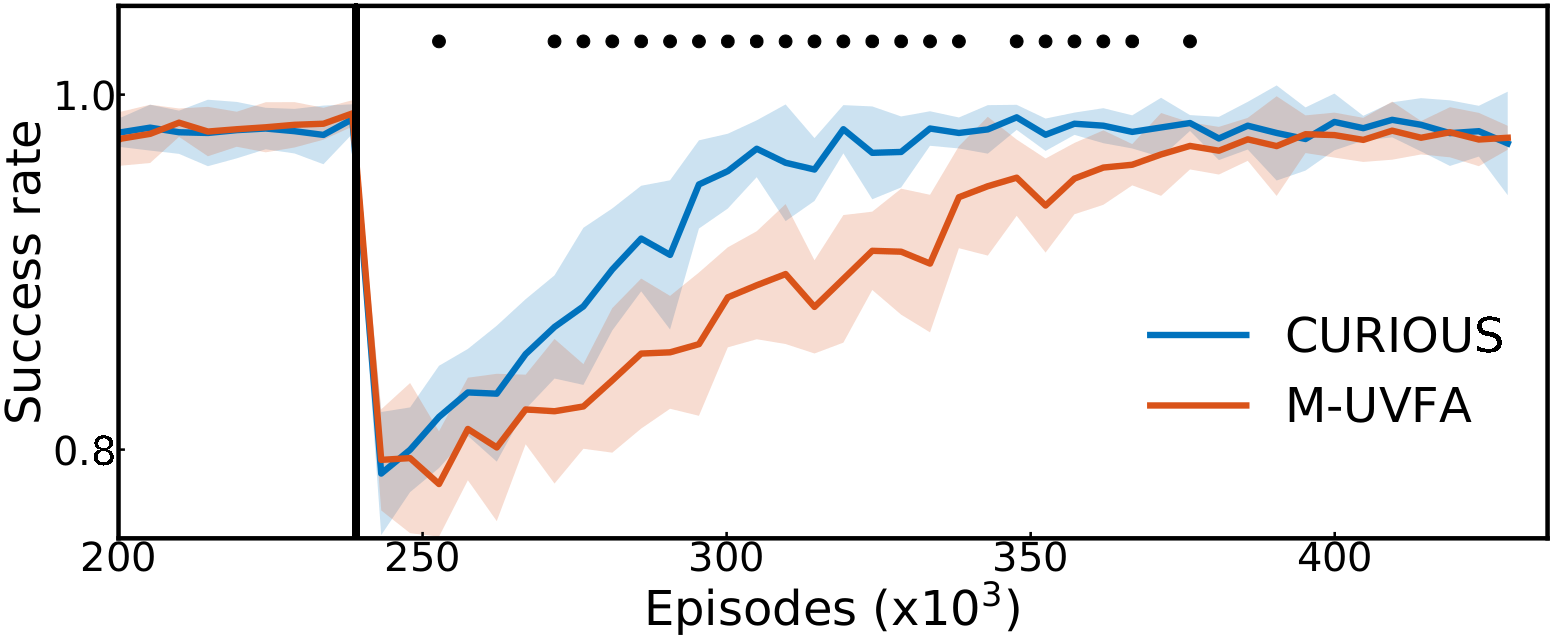

Resilience to Forgetting and Sensory Failures

Using absolute learning progress measures enables the agent to detect drops in performance. Here, we simulate a time-locked sensory failure: the sensor reporting the position of one of the cube is shifted by the size of a cube. The performance on the Push module related to that cube (one of the four modules) suddenly drops, making the average success rate over all modules drop by a quarter (see figure below). We then compare M-UVFA (random module selection and replay) and CURIOUS (using LP) during the recovery. CURIOUS manages to recover 95% of its pre-perturbation performance 45% faster than its random counterpart.

Resilience to sensory failure: Recovery following a sensory failure. CURIOUS recovers 90% of its original performance twice as fast as M-UVFA. Dots indicate significant differences in mean performance (Welch's t-test, 10 random seeds). Mean and standard deviations are reported.

Discussion

As noted in Mankowitz et al., 2018, representations of the world state are learned in the first layers of a neural network policy/value function. Sharing these representations across all modular goals explains the important difference between the M-UVFA encoding and the use of multiple module-expert policies. However, learning all modules in the same policy might become difficult as the number of modules increases, and when modules are different from one another (e.g. using different sensory modalities). Catastrophic forgetting can also play a role, as previously mastered modules might be forgotten because the agent targets them less often. Although this last point is partially mitigated by the use of absolute learning progress for module replay, it might be a good idea to consider several modular multi-goal policies when the number of modules increases.

CURIOUS is an algorithm able to tackle the problem of intrinsically motivated modular multi-goal reinforcement learning. This problem has rarely been considered in the past, only MACOB targeted that problem and proposed a solution based on population-based and memory-based algorithms. It is a problem of importance for autonomous lifelong learning, where agents must learn and act in a realistic world with multiple goals of different types and different difficulties, without having access to the reward functions.

In the future, CURIOUS could be used in a hierarchical manner. A higher-level policy could feed the sequence of modules and goals for the lower level policy to target. This would replace the current one-step policy implemented by a multi-armed bandit algorithm.

CURIOUS is given prior information about the set of potential modules, their associated goal space and the reward function parameterized by modules and goals. Further work should aim at reducing the importance of these priors. Several works go in that direction and propose autonomous learning of goal representation (Laversanne-Finot et al., 2018, Nair et al., 2018). Goal selectione policies inside each modul could also be learned online using algorithms such as SAGG-RIAC or GoalGAN.

Conclusion

This blog post presents CURIOUS, a learning algorithm that combines an extension of UVFA to enable modular multi-goal RL in a single policy (M-UVFA), and active mechanisms that bias the agent’s attention towards modules where the absolute LP is maximized. With this mechanism, agents spend less time on impossible goals and focus on achievable ones. It also helps to deal with forgetting, by refocusing learning on modules that are being forgotten because of model faults, changes in the environment or body changes (e.g. sensory failures). This mechanism is important for autonomous continual learning in the real world, where agents must set their own goals and might face goals with diverse levels of difficulty, some of which might be required to solve others later on.

Cite this blog post

@article{colas2019curious,

title={ {CURIOUS}: {I}ntrinsically {M}otivated {M}odular {M}ulti-{G}oal {R}einforcement {L}earning},

author={Colas, C{\'e}dric and Fournier, Pierre and Chetouani, Mohamed and Sigaud, Olivier and Oudeyer, Pierre-Yves},

journal={Proc. of ICML},

year={2019},

}

References

- Intrinsically Motivated Goal Exploration Process. Forestier et al., 2017.

- Universal Value Function Approximators. Schaul et al., 2015.

- Hindsight Experience Replay. Andrychowicz et al., 2017.

- Unicorn: Continual Learning with a Universal, Off-policy Agent. Mankowitz et al., 2018.

- Modular Active Curiosity-Driven Discovery of Tool Use. Forestier et al., 2016.

- Continuous Control with Deep Reinforcement Learning. Lillicrap et al., 2015.

- Curiosity Driven Exploration of Learned Disentangled Goal Spaces. Laversanne-Finot et al., 2018.

- Visual Reinforcement Learning with Imagined Goals. Nair et al., 2018.

- Automatic Goal Generation for Reinforcement Learning Agents. Florensa et al., 2017.

- Active Learning of Inverse Models with Intrinsically Motivated Goal Exploration in Robots. Baranes and Oudeyer, 2013.